When examining the dark crevices of London’s history, there’s no shortage of stories about decrepit neighborhoods and criminal networks, especially along the 19th-century docks and poorer areas of the great city. These notoriously seedy backdrops have set the scene for many a gruesome tale—from Jack the Ripper to the Yorkshire Witch—and remain some of the most captivating, even by today’s standards. So, it’s no surprise the grim underworld of the resurrection men also thrived during this time of desperation, darkness, and morbid opportunity. Sometimes referred to as body snatchers, the resurrectionists were people who stole corpses from local graves and then sold them to physicians, teachers, and scientists trying to push new boundaries in the medical world. Despite the pervasive level of disease in the 19th century, not much was known about anatomy or surgical practice, a reality that soon gave rise to increased medical and scientific inquiry. While the pursuit itself was noble, it did have one flaw—it must rely on body snatchers for a fresh supply of human cadavers. Because bodily donations after death were nonexistent during this era, researchers were willing to pay handsomely for such scarce materials. And as luck would have it, it seemed the city had just enough desperate people around to fuel such a criminal network of supply and demand. The relationship was so lucrative, in fact, stealing corpses became something of an epidemic, and suddenly the greatest concern of a grieving family was not to say farewell to a loved one, but to safeguard their remains.

In truth, body snatching became so pervasive in London during the 19th century (and around the world) that the U.K. was forced to take extreme measures against the resurrectionists and the practice as a whole. Not to be confused with grave robbers—who dug up the dead to steal their valuables—the resurrection men were solely interested in the corpse itself. And although the work was dirty and dangerous, the pay for delivering a fresh body to a local hospital or laboratory could easily bring in as much as £25, or two months pay, making the work of a body snatcher well worth the risk. And for many desperate individuals living in the bleak squalor of 19th century London, the opportunity to make a buck off the dead was simply too good to pass up.

In truth, body snatching became so pervasive in London during the 19th century (and around the world) that the U.K. was forced to take extreme measures against the resurrectionists and the practice as a whole. Not to be confused with grave robbers—who dug up the dead to steal their valuables—the resurrection men were solely interested in the corpse itself. And although the work was dirty and dangerous, the pay for delivering a fresh body to a local hospital or laboratory could easily bring in as much as £25, or two months pay, making the work of a body snatcher well worth the risk. And for many desperate individuals living in the bleak squalor of 19th century London, the opportunity to make a buck off the dead was simply too good to pass up.

But stealing a corpse from inside a buried coffin is no easy task, and to really understand why someone would go to such lengths, it’s important to consider the cultural climate at the time. The Industrial Revolution in Britain was a massive affair, and immigrants continually streamed in from Ireland and other continents, looking for work and the hope of a fresh start. Though not ideal, laboring on the docks or in local factories offered opportunity and the chance to get ahead in the new world. Of course, resources, money, and lodging were also scarce, a combination of factors which exposed people to injury, infection, and starvation. As a result, sickness was rampant during this time, and the death rate spiked at precisely the same time modern medicine was trying to make some significant advances. In this way, the two events fed on one another—the more illness spread, the more medical knowledge was needed. It was not uncommon to see dead bodies all over the city, in the Thames, on the streets, thrown sloppily by graveyard doors, and yet the raw materials used in anatomical studies were hard to come by. As stipulated by the Murder Act of 1752, it was only legal to use the bodies of executed criminals in any sort of anatomical experiments or dissection—using anything else was forbidden and considered highly immoral and deplorable. And so, the clever resurrectionists began to ponder the how they might supply cadavers to the medical world through illegal means.

But stealing a corpse from inside a buried coffin is no easy task, and to really understand why someone would go to such lengths, it’s important to consider the cultural climate at the time. The Industrial Revolution in Britain was a massive affair, and immigrants continually streamed in from Ireland and other continents, looking for work and the hope of a fresh start. Though not ideal, laboring on the docks or in local factories offered opportunity and the chance to get ahead in the new world. Of course, resources, money, and lodging were also scarce, a combination of factors which exposed people to injury, infection, and starvation. As a result, sickness was rampant during this time, and the death rate spiked at precisely the same time modern medicine was trying to make some significant advances. In this way, the two events fed on one another—the more illness spread, the more medical knowledge was needed. It was not uncommon to see dead bodies all over the city, in the Thames, on the streets, thrown sloppily by graveyard doors, and yet the raw materials used in anatomical studies were hard to come by. As stipulated by the Murder Act of 1752, it was only legal to use the bodies of executed criminals in any sort of anatomical experiments or dissection—using anything else was forbidden and considered highly immoral and deplorable. And so, the clever resurrectionists began to ponder the how they might supply cadavers to the medical world through illegal means.

While highly distasteful, body snatching during this time was not a felony. If caught, the offender would likely receive a fine and possible jail time rather than a heavy sentence or execution. The authorities typically turned a blind eye, mostly because they didn’t have the time nor the inclination to focus too heavily on something so common. This reality combined with the high demand for bodies turned the art of body snatching into somewhat of an epidemic.

Refrigeration in those days was almost non-existent, which made the procurement of fresh bodies especially challenging. Resurrectionists had to work fast, usually in the pitch of the night, often working in teams to locate dark mounds of newly turned earth and gain access to the grave. After the burial, most grieving families refused to put up gravestones for the first few months out of fear that flesh vendors would notice the new stones and target the site. Sometimes the resurrectionists would send female conspirators to spy on funerals, so they could scout the exact underground location of the coffin and report back about how to best retrieve the body. Grieving families would often pay a sentinel to watch over the premises at the conclusion of the ceremony, at least for a few weeks until the body had begun to decompose. The best score for a body snatcher was to locate a mass grave designated to the poor because their coffins were simply stacked together in one big hole and left mostly unsupervised.

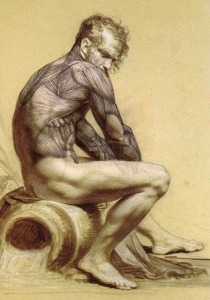

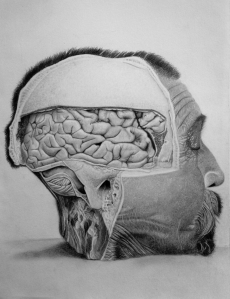

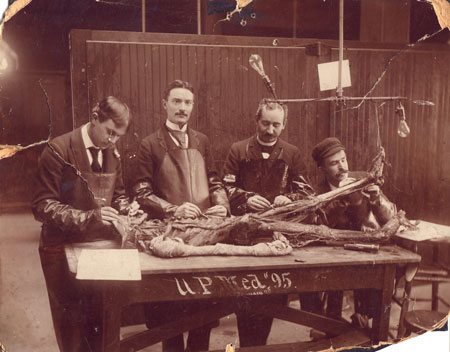

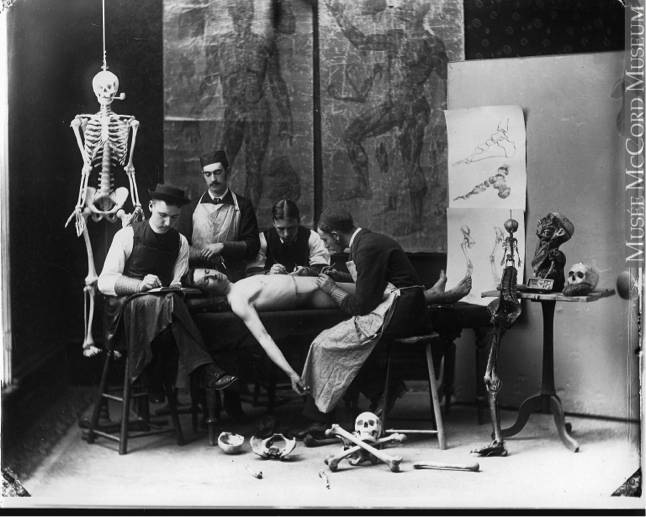

According to researchers at the University of Cambridge, who have assembled evidence from real excavations from the 1600s to 1800s, the archeological proof of body snatching is overwhelming and expressive of what medical examiners hoped to gain. Stolen cadavers were apparently used for all sorts of procedures, from amputation to surgical approaches, showing evidence of craniotomies where the skull had been opened up to access and study the brain and middle ear structures. As a key part of scientific understanding, anatomy involved learning about organ function and how bodies could sustain life during precarious operations. Reclaimed bones showed many things, including fine cut marks on the skull where the muscles had been peeled away from the bone with great intention and precision. One skeleton had been purposefully decapitated through the spine with a saw, for reasons no one really knows. And many sets of bones were incomplete, suggesting the remains were not always kept together, while other parts were carefully preserved in chemicals so they could be referenced in future pathology. In this way, the quality of life offered to the living happened largely through the study of the dead, a fair price to pay in the minds of many.

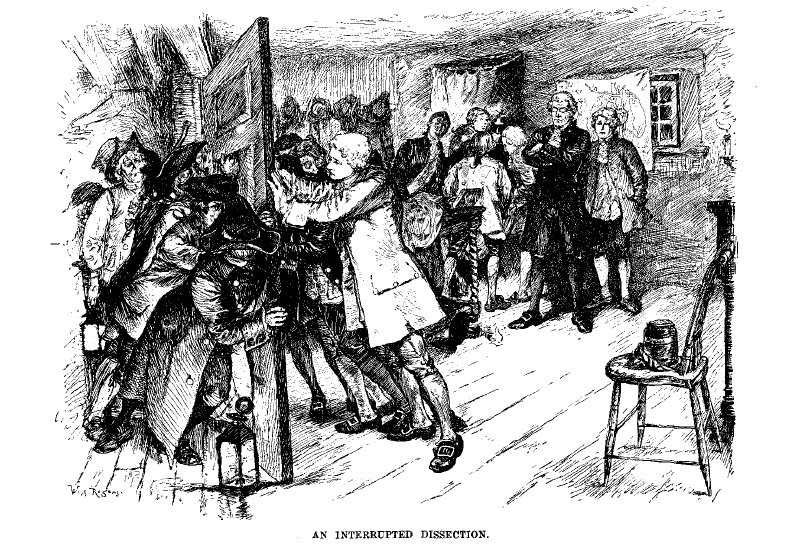

But the resurrectionists were not just bleary eyed crazies with shovels looking to make a buck—they were medical students, clever criminals, and middlemen who paid priests and undertakers for bodies, crafty beyond belief and often going to gruesome lengths to retrieve their valuable prizes. Their work was dangerous, dirty, and difficult—especially because it had to be done quickly and secretly so the body would retain its shape and no “resurrection riots” would erupt in the neighborhoods. As a result, they usually worked in groups, digging vertically several feet from the grave, like a tunnel, down to the head of the coffin, where they would break the lid, attach a long metal hook to the body, and literally pull the corpse through the hole to the surface. The clothes of the dead were then tossed back in, the opening covered with turf, and the body ferried away to its real final resting place. And when a visiting family arrived at the grave, they did not see the little patch of tossed earth several feet away and felt reassured, congratulating themselves on escaping the body snatchers entirely.

To the modern mind, the notion of dissection and anatomical study may not seem terribly wicked, but in the 19th century, it was viewed with horror. Body snatching was greatly feared by anyone who buried a loved one, and the reality of losing a family member’s body to such a fate could inflict profound psychological pain on those left behind. And for the more religious among them, the belief that the fate of a corpse determined that of the soul made the notion of dissection exceedingly disagreeable, as the person’s spirit would be doomed to wander without hope of ever gaining a real, religious resurrection or entrance into the beyond.

Aside from paying people off or simply guarding the grave until the body reached decomposition, people would go to great measures to avoid being victimized by body snatchers. To make the resurrectionist’s job harder, the corpse might be placed in a patent coffin made of heavier material like iron and—with the right amount of money—interred in a mausoleum or caged lair with locked metal doors. For those who couldn’t afford such opulent protection, a mortsafe resembling an above-ground cage was invented in 1816 to be built around the buried coffin—a precaution especially popular in Scotland. Also known as a “zombie cage,” these contraptions whimsically suggested they were built as a way to keep the dead from escaping, when in fact the reverse was true. Mortsafes would be set up for several weeks until the body was fully rotting, and then they could be conveniently reused. An example of an original mortsafe still sits in the Marischal Museum in Aberdeen, Scotland.

And for those who preferred the offensive to the defensive, a device known as a coffin torpedo could be set up which would put up a barrier between the cadaver and a body snatcher. Also known as grave torpedoes, coffin guns, or cemetery alarms, these explosive devices would sit on the lid of a buried coffin and fire lead balls at anyone who tried to dig it up, much like a shotgun loaded underground. Sometimes they were packed with gunpowder and had the ability to instantly kill any person stupid enough to mess with the grave. Other kinds of booby traps or protective snares in the form of sharp objects or broken glass could be attached to cemetery walls and placed strategically around the graves.

The situation reached epic proportions around 1828 when two men named Burke and Hare murdered 16 people over a period of ten months in Scotland, all for the purpose of selling their fresh bodies to a local doctor for his dissection and anatomy lectures. Then in 1831, a group of body snatchers dubbed the “London Burkers” copied the modus operandi of the two killers, luring unsuspecting victims back to their dwelling and murdering them in cold blood. Their bloody enterprise became so extreme, the fresh body of a 14-year-old boy—which had not even been buried—showed up at the King’s College School in the Strand. It was at this harrowing point that the Anatomy Act of 1832 was passed by Parliament, giving teachers, doctors, students, and scientists freer license to obtain willing or unclaimed bodies through legal and regulated means. A body might be willingly donated by the family or the corpses of unidentified individuals from hospitals, prisons, or workhouses could be granted to certain organizations through an official request process. And sometimes, people would donate their own bodies in the name of science, allowing studies to advance on things like nerve structure and circulatory systems.

And so the resurrectionists found themselves out of work, as the government began to scrutinize and regulate the passing of dead flesh. But not everyone was pleased with the civilized handling of the process, and there were many local citizens who found the decision to be repulsive and objectionable. In 1840, a furious mob protesting the Act attacked an anatomical establishment in Cambridge, vandalizing the premises as a way to illustrate their belief that the body snatcher would not be dissuaded, only forced to focus on stealing the corpses of the poor who could not afford better accommodations after death. In this way, the issue had morphed into one based on class, and that left a bitter taste in the mouth of many English.

Body snatching also existed in the U.S., and in typical fashion, racial segregation was a major factor in how the process played out in American graveyards. Burying grounds were clearly delineated according to race, and in places like New York’s Potter’s Field, the free blacks as well as the slaves were buried in separate areas where their remains were predictably not supervised against intrusion and theft. At the end of the American Revolution in 1783, about one fifth of New York City’s population was black, most of whom were slaves. When the city was constructed under Dutch and English supervision, the work was largely completed on the scarred backs of Africans. Because of their low social standing and lack of legal recourse, their bodies were only allowed to be buried outside the city limits, which also made them an easy target for roaming body snatchers.

But the second most affected group in U.S. were the poor whites who could also not afford the price of protection. The blatant activities of medical students and physicians in New York City finally came to head in 1788 when a young boy peered in through a hospital window and saw a man dissecting a human arm. When the doctor saw the voyeur, he waved the appendage at the boy and taunted him, saying it belonged to his mother who had recently died. When the boy ran home and told his father, the men of the town dug up the woman’s grave and found her missing. During the Doctor’s Riot of 1788, an angry mob broke out around the hospital, and upon finding many bodies at various stages of dissection, pulled physicians into the street where they threatened bodily harm. The police were forced to lock up the physicians as a way to keep them safe from the enraged townspeople.

In other parts of the world, the reasons for body snatching had more to do with custom and ancient practice than profit. As recently as 2006, reports of body snatching have surfaced in rural areas of China where the corpses of young women have fetched high prices in a ritual known as ghost marriage. It is believed deceased and unwed males must move on into the after life with some kind of wife, and the cadavers necessary to complete this ritual can only be found on the black market. In 2007, a man was actually arrested by Chinese authorities for killing six women and selling their bodies as “ghost brides.” As for other countries like Cyprus and Australia, bodies of former leaders of particularly influential people have been stolen from graves to be cut up as sold as keepsakes for the highest bidder. And in the case of a 16th-century French scholar, Andreas Vesalius, who began stealing remains from a Paris cemetery, the main purpose of body snatching was to satisfy his own curiosity about medicine and complex world of anatomy. He asserted he only had ancient texts to rely on for knowledge and felt it was acceptable to steal bodies, boil them down to bones, and reconstruct them like a jigsaw puzzle, all in the name of progress.

While new legislation and stricter guidelines have certainly put a major dent in the body snatching industry, the practice lingered here and there throughout the 20th century and was even detected just a decade ago. In 2006, four men in New York City were charged with selling body parts from the morgue to buyers from the transplant industry, all without any sort of permission or consent. Today, a clandestine market still exists for cadavers and body parts in both America and abroad. Although most governments prohibit the buying and selling of dead bodies, this illegal flesh trade can fetch up to $100,000 on the black market or the darknet. Citing reasons like cannibalism, necrophilia, or experimentation, the new breed of body snatcher is faced with a much more nefarious demand.

And the rest is history.

Will read soon 🤙🤙🤙🤙

Sent from Yahoo Mail for iPhone

LikeLike

Interesting to see the ideas people have around death and the soul. Really enjoyed this.

LikeLike

What a brilliant writer!! Loved starting my morning with a little body snatching history!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you dear reader!!

LikeLike