Medieval Europe could be a frightful place for a woman of strength, especially one with the wisdom of a midwife and the proclivities of a healer. Intensified by her status as an elderly widow in 16th-century Germany, Walpurga Hausmännin made the perfect witch. Accused of over forty heinous crimes against children like vampirism and murder, her graphic confessions were even more shocking, bringing forth stories of demonic sex, cannibalism, and heresy. But the historical question remains—was she in league with evil spirits or just an unfortunate figure caught in a maelstrom of puritanical fear? Either way, the story of Walpurga Hausmännin provides an unforgettable glimpse into the dark mythology of witchcraft and the horrific violence that made it real.

Living as a respectable midwife for almost 20 years, Walpurga Hausmännin was a fixture in the Bavarian town of Dillingen until that fateful day when she was accused of witchcraft. Although it’s unclear who started the rumor, suspicion grew when she delivered several stillborn infants in a short period of time—a tragic situation that drew the attention and fear of her provincial community. As gossip began to fly, Hausmännin’s reputation grew, and she soon found herself in chains, facing serious charges of maleficia for infanticide, destruction of the harvest, and the death of her neighbor’s cattle. “Kindly questioning” soon gave way to severe torture, and it wasn’t long before Hausmännin buckled under the pain and admitted everything, offering one of the most disturbingly detailed confessions in the history of witchcraft.

According to her own admissions, her bond with the Devil had been forged some thirty years before in 1556 when she sought the company of a neighbor in the lonely days following her husband’s death. Through flirtation and provocative behavior, she had convinced the man to meet her for a lover’s tryst at her nearby home. But when the agreed upon evening arrived, it wasn’t her neighbor who appeared but rather a demon in disguise named Federlin who tricked her into having sex with him. During intercourse, she felt his cloven hoof—cold and hard like a piece of wood—and she knew it was a figure of evil with whom she slept. In her fear, she called upon the name of Jesus and the devil immediately fled.

The rest of her confession was enough to curl the toenails of even the most amoral citizen, an unraveling of a sorceress’s darkest secrets. As expected, Federlin appeared the next night and took Hausmännin again, promising her security and protection if she pledged herself to him body and soul. She did, and they sealed the filthy pact with a toast, drinking wine and dining on the roasted flesh of an innocent child. Despite her protests, she was persuaded to serve the Devil in many ways—seeking the destruction of her neighbors, their children, and their livelihood.

Federline appeared constantly, forcing her to have sex in public places and giving her an evil ointment to be used in her machinations against others. Hausmännin confessed to injuring both animals and people by secretly rubbing the wicked salve on the bodies of young mothers at her mercy and on pristine newborn infants under her care, all of whom died soon thereafter. She admitted to killing many children during her time as a midwife, infecting them with her villainous medicine and even sucking their blood with other witches, afterward using their hair and bones in her diabolical spells.

It was the year 1587 and shocking though her confession was, what proved most revolting to her community was her brazen rejection of God. Hausmännin had apparently not only killed countless innocents with her sorcery, but she had smuggled out church sacraments and symbols—using them in Black Masses with the Devil—and had renounced all of Christendom along with any chance of salvation. Sex with a demon was one thing, but offering the Body of Christ to the Evil One was beyond comprehension for the folks of 16th-century Bavaria, and the imperial court along with Archbishop of Augsburg immediately sentenced her to death. Her property was confiscated, and she was imprisoned in the local dungeon to await her day of execution.

Given the extent of her testimony and the religious nature of her crimes, Hausmännin could not be buried as a Christian, a denial most people of that time found deeply upsetting. In theory, she would have no chance of being resurrected to heaven because her body would suffer the stiffest penalty possible—to be burned at the stake. But that wasn’t all. For witches whose crimes were considered especially heinous, there were additional torments in store.

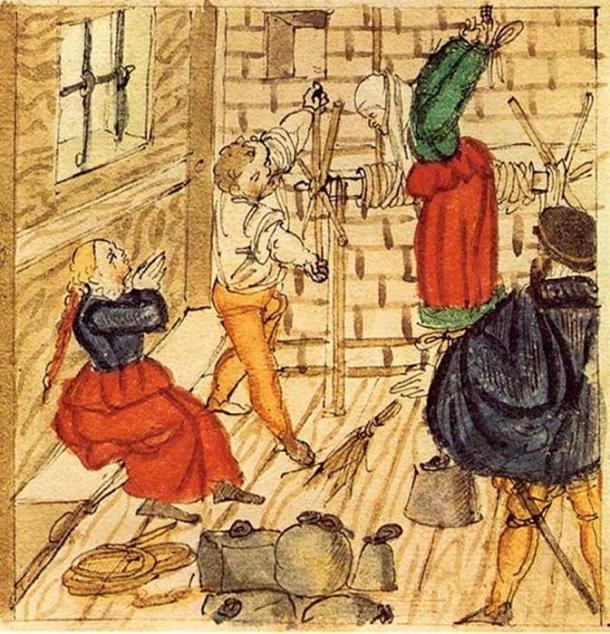

In classic medieval fashion, she was seated and tied down to a rickety cart and rolled through the streets of the city, paraded as a confirmed witch before a frenzied and jeering crowd. While making her way to her execution site, Hausmännin’s body was mutilated five separate times with red-hot iron tongs: first outside town hall where, her left breast and her right arm were torn and later, her right breast. As her wretched journey continued, the crowd stopped again to rip her left arm apart, and when the cart finally arrived at the funeral pyre, her left hand was brutally maimed as well.

Grisly though it was, the widow Hausmännin’s sufferings were not over yet; she must be punished for her betrayal of the midwife’s oath to heal and protect, a pledge she had officially taken some 20 years before by placing her right hand on a Bible. And so, this knavish right hand was cut off in front of the crowd, and the bloody, disoriented woman was firmly lashed to the rough wooden stake where she was set afire for all to see, the crowd assembling upwind of the flames so as not to be whipped by black smoke and molten fat.

Even in ash, her body was reviled and had to be removed from the ground so as not to be used in any other foul plot. Consequently, the executioner shoveled up her remains and dumped them into the closest stream where they were carried away by the rushing water, never to collect again.

Looking back on Hausmännin’s story, it seems likely she was a victim of hearsay rather than a perpetrator of heresy. But what’s most striking about her case is the level of detail provided in her confessions, all of which fit impeccably into the ongoing narrative of witchcraft. How did Hausmännin manage to chronicle such a perfect portrayal of the occult?

She provided a flawless description of the Devil as a great prince, richly attired with a gray beard and seated in an ornate chair, and detailed the contract she wrote in her own blood. She related so many specifics—how the town looked below when she rode a pitchfork overhead, how she fornicated with the demon Federlin in her dark prison cell, how she watched specific victims die, and how she never used salt when dining with the Devil. Granted, Hausmännin had been raised a Catholic, but it’s unclear why she knew that salt, a religious symbol of sanctity and protection, was forbidden on the witches’ Sabbath. How did such a respectable woman come to know these dark details of sorcery? And, more importantly, why did she admit it?

Was Walpurga Hausmännin just a wildly imaginative woman with a penchant for fabrication? Maybe she was a just desperate victim looking to ease the pain of torture. (After all, thumbscrews can be particularly persuasive). Or perhaps she suffered from delusions of wickedness, recreating the scenes of depravity she believed were true. Regardless of her reasons, the townspeople found exactly what they were looking for, and her confessions have been sealed in the annals of dark history. But there is still one remaining question that lingers in the mind of anyone who hears her story. Did she really believe herself to be a witch? Her accusers were clearly demonstrating their own piety and concern for order through these proceedings, but what on earth did old lady Hausmännin’s stand to gain?

While shocking, the graphic story of Walpurga Hausmännin does not deviate much from the classical notion of medieval justice for witchcraft. Her confessions exemplified the classic relationship between witch and devil during the Middle Ages, a pairing that would serve as a template for the witch hunts of Early Modern Europe and Colonial North America. If she had wanted her inquisitors to believe her guilty beyond the shadow of a doubt, she did her job well by conjuring up just about every preconceived notion of wickedness known to Christendom. By the time she was through confessing, they couldn’t chop the wood fast enough.

In Germany, witchcraft would remain punishable by law into the late 18th century, providing the perfect framework to explain upsetting occurrences of sickness or death that might otherwise be attributed to God’s will. Witch hunts throughout history were pretty universal for thousands of years but were really solidified when the Catholic Church of Europe established a government group in the 12th century whose aim was to snuff out heresy at any cost. Over a period of over 400 years, approximately 70,000 people were executed in the name of righteousness. All in all, Hausmännin’s life and those who suffered under similar circumstances stand as a grave testament to the depth of religious fear and the extraordinary measures people took to defend themselves from evil.

And the rest is history.

This story of true history is rattling! To know this really happened in history is beyond Dark!! However, written so amazingly by Ms Shulman That you don’t want it to end 👍💕

LikeLike