The odor of scorched gunpowder filled the air in the morning, it lay in soft, blue clouds over the earth of my people.

—Darryl Babe Wilson

One of the greatest things about dark history is its ability to deliver a shock, even when it feels like we’ve heard it all. Its rawness refreshes the senses with the realization that human memory is often a convenient and forgetful thing, particularly around highly romanticized eras like the California Gold Rush. Listening to the old stories of starry-eyed prospectors, covered wagon trains, and gunslinging vigilantes is enough to have anyone waxing nostalgic about how the true spirit of California came to be. Heck, San Francisco named their football team after the famous ’49ers, and if you find yourself in the city this holiday season, you can take in John Adams’s new opera—Girls of the Golden West—about a diverse group of immigrants all trying to hit it big. But the Raven is here to remind us of the steep price we paid for those golden nuggets and the painful legacy they left behind.

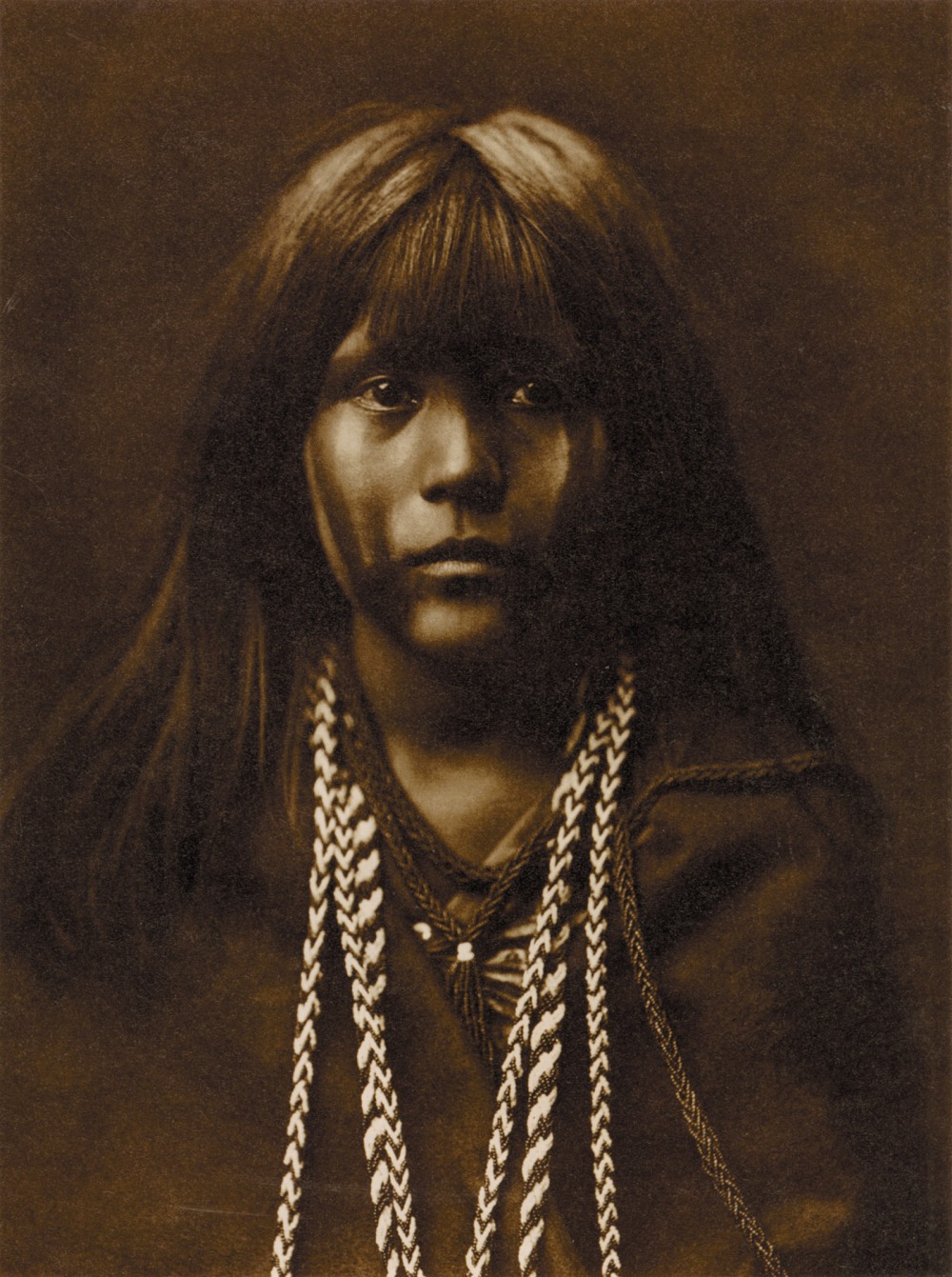

One of the most challenging aspects of American history is determining exactly when it began. Clearly, the nation’s official birthday on July 4th, 1776 was just one monumental occasion in a much larger and more complicated narrative. There are certain defining moments we all take for granted—the Revolutionary War, the Emancipation Proclamation, women’s suffrage, the Civil Rights Act, Armstrong on the moon—and yet these events are floating on the surface of a deep and sanguine ocean of hidden truths. In fact, for such a young nation, packed with so many laudable accomplishments, America has a surprisingly vile underbelly. Along with the transatlantic slave trade, the most heinous scar it bears is the genocide of native people who lived for centuries upon centuries before popular “history” even began. But they were wiped out so quickly, their lack of written language made it nearly impossible for them to document any of their experience.

We know the settlers of Jamestown and Plymouth set the tone for the nation’s dominant cultural identity, but the truth is the Spanish Empire had penetrated deeply into the Americas and started scooping out its treasures long before that. And while the recent discovery of an old footprint in Mexico suggests modern humans may have been in the Americas as early as 40,000 years ago, as a civilization, we can only reflect back as far as the initial struggle between the first European settlers and the indigenous people of this great land. Although history has dubbed it the “New World,” this period really just marked the extension of an ancient one into a terrifying episode of human expansion—a monumental clash of the old and the new.

Most people recall the Gold Rush as one of the most charming periods in California history when the future was bright and shiny and filled with possibility—when some 300,000 rugged, adventurous people converged on the region to make their fortune through hard work and a big dose of luck. Sutter’s Mill in Coloma is celebrated to this day as such and woven into the curriculum for schoolchildren who are told the story of how one man, a simple carpenter from New Jersey, found flakes of gold in the American River at the base of the Sierra Nevada Mountains and started a movement that would ultimately shape the culture and economy of the state—and the larger United States.

While it’s true the California Gold Rush of 1848 marked a pivotal moment in the state’s history, it also initiated one of the most harrowing genocidal periods in the entire history of Native American life. Dubbed “the greatest disgrace to mankind” by transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau, this period of discovery delivered a decidedly different experience to the natives by trading riches and opportunity for oppression, discrimination, slavery, rape, and outright murder. This barbarism toward the indigenous people of North America cannot be overstated. Over the 27 years from 1846 to 1873—marking the period when California settlers began making themselves at home in Mexican California—the local Native American population declined by over 80 percent, from around 150,000 to perhaps 30,000. In 1870, the federal census put the population of California Indians at 7,241. This period would come to represent the most potent mass murder of their people, bringing many tribes to the brink of extinction.

On the morning of January 24, 1848, James Marshall found gold as he was working construction at Sutter’s Mill. Even though the enterprise was relatively small, it employed many men, including the Miwok Indians (or Mokelumne) who labored alongside the white men to process and produce lumber for the area. At that time, there were approximately 4,000 Europeans living in all of California and only about 400 of them were bonafide Americans. But by the end of the following year, some 80,000 immigrants had traveled over land and sea to enter the golden state, from nearby places like Mexico as well as far-flung destinations like China and Australia. Although the majority of the goldfields being discovered lay in the ancestral lands of tribes like the Karuk, Yuki, Wintu, Maidu, Modoc, and Miwok, Johann Sutter convinced the Mexican governor to grant him 48,000 acres—or 76 square miles—of land in the Sacramento Valley for the purpose mining gold.

Prior to Sutter’s request for land, many different tribes were living in the region, with stable villages, social systems, and mostly peaceful territories. Because California Indians had been spared the majority of sickness brought in by the first few waves of Europeans, they lived quite comfortably on the far side of the tall mountains and impassable deserts of the northern region. Scholars agree that what is now the Bay Area likely held tens of thousands of Ohlone, Miwok, Patwin, and Wappo people who thrived on the productive wetland ecosystems and spoke over 300 dialects of 100 distinct languages—one of the highest concentrations of cultural diversity in the world. But for Sutter, these people meant labor, which he garnered through trade and the appointment of capitanos who he paid with useless pieces of tin once they brought him the muscle. Although the Miwok and Maidu natives did most of the work on the ranch—building forts, plowing fields, planting crops, tending livestock, weaving cloth, making blankets, operating the distillery, running the tannery, hunting venison—it was not done out of pragmatism. Instead, they labored under a system that verged on slavery, with no real pay and horrendous conditions.

A manager at the mill named Heinrich Lienhard wrote in a first-hand account, “I had to lock the Indian women and men together in a large room to prevent them from returning to their homes in the mountains at night. Large numbers deserted during the daytime.” In fact, the conditions were so similar to those being endured by African Americans in other parts of the country, another overseer wrote, “The Indians of California make as obedient and humble slaves as the Negro in the south. For a mere trifle, you can secure their services for life.”

Men, women, and children were kept against their will, fed in troughs like animals, raped and beaten, and forced to work as indentured servants under the Act For The Government and Protection of Indians which ensured their captivity. This led to widespread kidnapping of native children who could be put to work, noted by a settler in 1858: “In coming into the valley, on the first occasion, I met a man with two Indian boys taking them off, and the third time I came on the trail, I met a man taking off a girl.” There are no records of these children ever being returned.

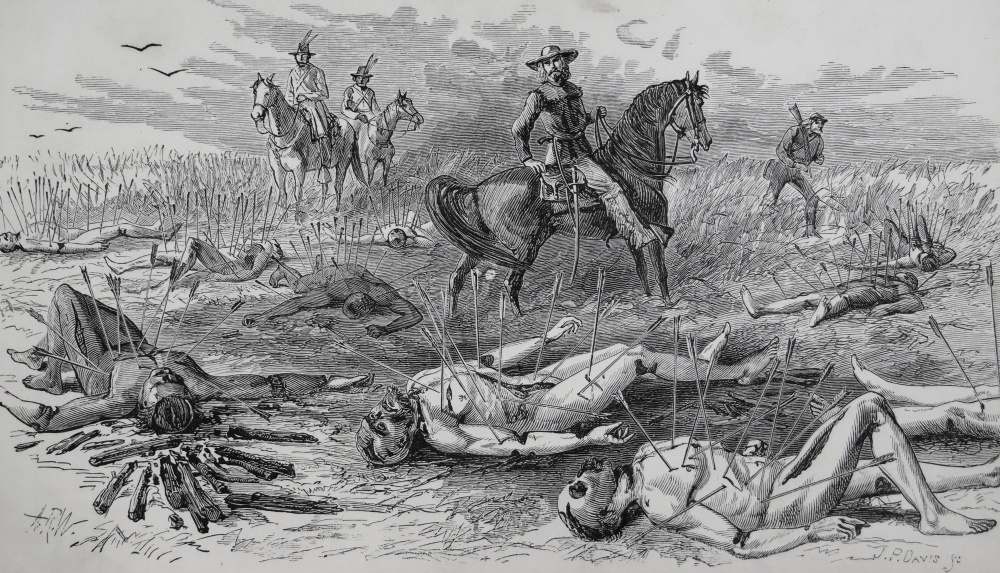

Just a few years before Sutter’s Mill was established, in April 1846, a violent incident took place along the Sacramento River that would set the tone for the grisly decades ahead. As Army Captain John Frémont—who would later become the first Republican Presidential candidate—led his men northward along the site near what is now Redding, they encountered a larger group of Wintu Indians who had gathered on the peninsula to harvest some spring salmon. Because the Indians had been moving as a tribe, there were many older people, women, and children among them. When the 76 well-armed white men confronted the natives, some of the warriors attempted to step in front of the elders to protect them. Frémont’s men fired on them with rifles until they ran out of bullets, at which point they jumped down off horseback and attacked the tribe with bayonets, and finally with butcher knives. They rode down any runners and killed them as well, all without losing one American soldier. This encounter led to the death of approximately 700 Indians and is historically noted as the first such act of extermination in a three-decade campaign of indigenous genocide.

The West began to symbolize opportunity for risk-takers, pioneers, and trail-blazers, all of whom came to define the American Gold Rush. But the California Indians did not share the values of the incoming settlers, who were mostly young white men following dreams of riches and success. For them, the native people were nothing more than savages, or dirty animals, who stood in the way of American progress and prosperity. This notion was perpetuated by the dominant culture which published propaganda in local papers and trained European immigrants to hate Indians. In his January 1851 message to the California legislature, Governor Peter H. Burnett promised: “a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the two races until the Indian race becomes extinct.” And to make matter worse, the gold appeared to dry up just a two years later in 1853, leaving bitter miners looking for purpose and more likely, someone to blame for their growing misfortune.

After the establishment of Sutter’s Ranch, gold began pitting the white man against the brown, and local militias were created to “protect” the prospect settlements from native invasion. In fact, the hateful and violent actions of well-armed squads combined with random killings by miners resulted in the extermination of over 100,000 Indians, a staggering loss of two-thirds of their population in just two years time. Ultimately, the settlers were afraid of the Indians, who they believed would jeopardize their financial and cultural future. To put it into perspective, the nine-year period of 1848-1852 brought in an estimated 24.3 million ounces of gold—or $6.9 billion worth of precious metal.

This was a mind-boggling number for the 19th-century mind. Any Indian who got in the way of this profit instantly found themselves on the wrong side of a gun. Truthfully, the Indians did not fully understand the value of the gold and were often taken advantage of by settlers who offered them glass beads and such instead of the money they were owed. But when the Indians caught on to the real value of the enterprise, “a war of extermination” became the solution to the “Indian problem.” This took shape through state-funded campaigns willing to pay $10 to $25 for proof of executed Indians in the form of scalps, heads, hands, or whole bodies.

And true to this goal, the natives were “melting away like the snows of the mountains” by 1859 as the Mendocino War took off and such men as the infamous Captain Walter Jarboe instituted murderous gangs in search of Indian blood, assuming names like the Placer Blades and the Humbolt Home Guard. As a notorious killer who led the “Eel River Rangers,” Jarboe was sanctioned by California Governor John Weller to lead a campaign for the permanent extermination of the Yuki and other neighboring tribes. Five months later, Jarboe presented the report on his work—along with an $11,143 bill for his services—stating he had killed 283 warriors and taken 292 prisoners, all of whom were sent back to the reservation.

California Historical Society

Although Jarboe made no mention of killing women and children, a first-hand account in the Alta Californian testified that he and his death squad had done precisely that: “The attacking party rushed upon them, blowing out their brains and splitting their heads open with tomahawks. Little children in baskets, and even babes, had their heads smashed to pieces or cut open. Mothers and infants shared the same phenomenon…. Many of the fugitives were chased or shot as they ran…. The children, scarcely able to run, toddled toward the squaws for protection, crying with fright, but were overtaken, slaughtered like wild animals and thrown into piles.” While Governor Weller’s silence appeared to sanction this behavior, the San Francisco Bulletin criticized Jarboe’s actions as a “deliberate, cowardly, brutal massacre of defenseless men, women, and children…”

But the truth was many settlers didn’t thrive during the Gold Rush and were having a hard time making money through prospecting. Many of them had come west to escape their criminal pasts and find a fresh start among a new population—but what they found instead were days full of back-breaking work and a life spent living in filthy, overcrowded shanty towns. They had migrated to California to find a better life—only to discover their own version of the Great Depression—and they often channeled this disappointment and anxiety into an irrational resentment of the natives. This justification helped them accept their dashed dreams and rationalize their racial brutality. It also helped them make ends meet, as they were paid well by the government to eliminate natives using nothing short of deadly force. In fact, between the years 1850 and 1860, the state of California paid about $1.5 million dollars towards the handling of the “Indian problem” through methods of violent, vigilante justice.

To make matters worse, John Sutter was known to be “fond of the young Indian women” who he often forced into having sexual relations with him and his men. Because the average prospector was in his early 20’s with no family to speak of—and because the female population in California during 1850 was only eight percent—the abduction and rape of native women skyrocketed. Even though Army soldiers were stationed on the reservations to protect them, one Lieutenant Dillion reported, “It is a common occurrence to have squaws taken by force from the place.”

Indian women were frequently assaulted by settlers which led to the spread of venereal disease throughout their tribes. As an editorial in the Marysville Appeal illustrated, “white settlers draw their supplies of kidnapped children and women for purposes of labor and lust… there are parties in the northern portion of the state whose sole occupation has been to steal young children and squaws… and dispose of them at handsome prices to the settlers who will willingly pay $50 or $60 for a young “digger” to cook or wait upon them, or $100 for a lively young girl.”

According to an 1859 petition sent by Tehama County settlers to the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, the agent in charge of the reservation was “compelling the squaws, even in the presence of their Indian husbands to submit to his lecherous and beastly desires,” thus introducing “among them diseases of the most loathsome character.” During the years between 1856 and 1858, one-fifth of the female Yuki population became diseased through rape and other physical abuse. Indian women were stolen to be harvest hands, servants, and camp wives, with no say in their condition or their future. Of course, this did not sit well with the native men who sought retaliation but were only met with systemized “killing sprees” by miners looking to push their agenda.

For anyone skeptical about the word genocide being applied to the Gold Rush era, there is the matter of statistics to reckon with. Officially speaking, this famous period lasted seven years—from 1848 to 1855—during which time there were fourteen separate massacres of Indians in the Northern California/Oregon region alone. This number does not even include episodes of mass violence in other parts of the country like Texas, Nebraska, and Idaho. Without the authority to arrest white settlers, U.S. Army soldiers had no power to pursue or punish those who had taken it upon themselves to exterminate the natives. And because the California legislature prohibited Indians from bearing witness against whites, it was virtually impossible to charge those suspected of wrongdoing, even when the atrocities took place in broad daylight. With a license to kill, the settlers had little fear of consequences and generally raped, murdered, and kidnapped Indians with impunity. No matter what term is used to describe this horrific period of bloodshed, the numbers don’t lie:

- 1850 Bloody Island Massacre: Nathaniel Lyon and his U. S. cavalry killed 100 Pomo people on Bo-no-po-ti island near Clear Lake, California, as they believed the natives had killed two local settlers who had been abusing and murdering members of the tribe. This incident led to a general outbreak of settler attacks against natives and a spike in mass killings all over Northern California.

- 1851 Old Shasta: Town miners killed 300 Wintu Indians near Old Shasta, California and burned down their tribal council meeting house.

- 1852 Bridge Gulch Massacre: 70 white men led by Trinity County Sheriff William H. Dixon killed more than 150 Wintu people in the Hayfork Valley of California, in retaliation for the killing of Col. John Anderson.

- 1852 Wright Massacre: White settlers led by the notorious Indian hunter Ben Wright massacred 41 Modocs during a “peace parley.”

- 1853 Howonquet Massacre: Californian settlers attacked and burned the Tolowa village of Howonquet, massacring 70 native people.

- 1853 Yontoket Massacre: A posse of settlers attacked and burned a Tolowarancheria at Yontocket, California, killing 450 Tolowa during a prayer ceremony.

- 1853 Achulet Massacre: White settlers launched an attack on a Tolowa village near Lake Earl in California, killing between 65 and 150 Indians at dawn.

- 1853 “Ox” incident: U.S. forces attacked and killed an unreported number of Indians in the Four Creeks area of Tulare County, California in what was referred to by officers as the “chastisement” of “our little difficulty.”

- 1854 Nasomah Massacre: 40 white settlers attacked the sleeping village of the Nasomah Indians at the mouth of the Coquille River in Oregon, killing 15 men and one woman.

- 1854 Chetco River Massacre: Nine white settlers attacked a friendly Indian village on the Chetco River in Oregon, massacring 26 men and a few women. Most of the Indians were shot while trying to escape. Two Chetco who tried to resist with bows and arrows were burned alive in their houses. Shortly before the attack, the Chetco had been induced to give away their weapons as “friendly relations were firmly established.”

- 1854 Ward Massacre: Shoshone killed 18 of the 20 members of the Alexander Ward party, attacking them on the Oregon Trail. This event led the U.S. to eventually abandon Fort Boise and Fort Hall in favor of the use of military escorts for emigrant wagon trains.

- 1855 Klamath River Massacres: In retaliation for the murder of six settlers and the theft of some cattle, whites commenced a “war of extermination against the Indians” in Humboldt County, California.

- 1855 Lupton Massacre. A group of settlers and miners launched a night attack on an Indian village near Upper Table Rock, Oregon, killing 23 Indians—mostly elderly men, women, and children.

- 1855 Little Butte Creek: Oregon volunteers launched a dawn attack on a Tututniand Takelma camp on the Rogue River, where between 19 and 26 Indians were slaughtered.

Equally as disturbing as the word genocide is the pervasive sense immunity some people feel when hearing it, as if it doesn’t concern them. They gloss over the facts and statistics, chide those who choose to illustrate them as “bleeding liberals,” and desperately try to protect themselves from feeling anything, let alone empathy for those who suffered so terribly. Why? Why not just look at what really happened, stare it straight in the eye, see it, and learn from it. Understand it. Teach it. While it’s important to find a passage through these unbearable memories, it is equally as imperative that we take time to stop and reflect on the level of darkness achieved at the hands of mortal men—not in ancient Rome or Greece or Israel, but in the United States just 160 years ago.

In no uncertain terms, the Gold Rush was a time of flagrant, psychotic disregard for the lives of the “other” whose greatest crime was their mere existence. Through an unfathomable brand of ignorance and hatred, grown men were able to justify ripping scalps from the heads of innocent babies as they ran for their lives, screaming for protection. Women and girls—from young to old—were thrown in the dirt, molested, and raped in front of their children, their husbands, their own mothers. If ever there were demons in the world, they found their way to California in the 19th century, where they mined for bloody gold in the hearts of godless men. Without the ability to bear witness to these atrocities and accept the gravity of their form, there will never be progress and there will never be peace.

It should be noted that the California Indians resisted the genocidal war being waged against them during this time, most famously during the Modoc War of the early 1870s. Having been forcibly relocated to a reservation, the Modoc people revolted and returned to their ancestral land in the lava bed region of the Siskiyou County. Under the leadership of Kintpuash, also known as Captain Jack, 150 native warriors fought valiantly against over 1,000 U.S. troops who tried to overtake them for months. But due to a lack of water, some tactical mistakes, and weakened Indian forces, Captain Jack was eventually captured and hanged execution style. The war cost the United States over $1 million and accomplished nothing but death on both sides.

Although the Gold Rush was certainly one of the most prolific periods of indigenous murder, it was really just an extension of an already violent system created by the Spanish missions of California. Officially, Indians were considered gente sin razon, or “people without reason,” uncivilized and in serious need of a proper baptism. Up and down the coast, Catholic zealots of the 1700s enslaved thousands of Indians by adopting them into their Christian “flock” and holding them hostage through floggings, imprisonment, and threats of death. In fact, the treatment was so brutal and inhumane, well over half of the 16,000 natives stolen by the Franciscan missionaries in the years between 1790 and 1800 died while in captivity. By 1818, 86 percent of all abducted natives met their demise at the hands of violent physical abuse or execution and were buried in mass graves behind the church. Those who survived were given Spanish names, dressed in blue uniforms, and forced to endure heavy, unpaid labor tanning hides, producing candles, laying bricks and tiles, crafting shoes, mending saddles, making soap, and any other chore that needed doing. Even though the Mission Era set a low bar for Indian dignity in the 18th century, the ensuing behavior of the Americans would take that bar to subterranean levels.

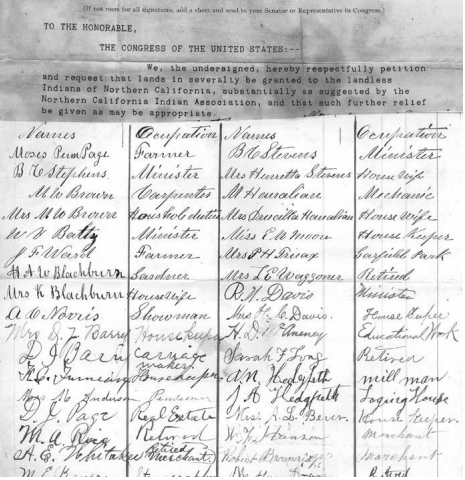

In 1850, when the world was rushing in to dig for gold in California, it was clear the Indians had become an even more significant problem than ever before, mostly because the monetary stakes were much higher. As a result, senators in Washington D.C. met in executive session to consider 18 treaties with Indians across the state of California. Just like those with foreign governments, these treaties had to be ratified by the Senate in order to be legitimized and respected. An unratified treaty had no force and could easily be ignored or forgotten. During these negotiations, the Indians agreed to give away 7.5 million of acres of land in exchange for the government’s promise of protection with adequate water and enough wild game to sustain their way of life. Even though this gifted land only constituted 7.5 percent of the total land area in California, the U.S. Senate chose to back out of the deal at the last minute and refused to ratify their treaties. Apparently, the senators were not sure if Mexico—from whom California was originally acquired—recognized native land titles. If they did not, then the Indians fell under U.S. sovereignty with any real legal claims to its territories. While this small loophole was enough to perk the government’s interest, the rush of California’s gold sealed the deal immediately. Why give the Indians land if it wasn’t absolutely necessary? And so, the treaties were rejected and languished without much attention for the second half of the 19th century. Although the Senate hoped these unratified treaties would remain secret and forgotten, they eventually leaked out to the media and even to the Indians themselves.

Demonstrating their obvious shame and ineptitude, the U.S. government “misplaced” the treaties for about 50 years until it was discovered in 1904 that they had actually sealed them “in confidence” within the Senate. But unrelenting researchers found them in the Office of Indian Affairs, which of course propelled the government to conveniently release them around the same time to avoid further scrutiny. Although Senator Thomas Bard of California was opposed “to spending any large amounts of money in furnishing lands to Indians who can get along without,” $100,000 was appropriated in 1906 to purchase the first of California’s Indian rancherias and another $50,000 followed in 1908. This gesture was meant to compensate for those unratified treaties from half a century ago, which had left Indians in a purgatorial state.

During this transitional time, some Indians were housed in the only two California reservations available—the Hoopa and Round Valley—while other existed independently outside their borders. These uncounted, non-reservation Indians were not citizens of the U.S. and had no legal rights, protections, or government support under the law. Some white reformers found this situation deplorable, noting the harsh living conditions of one 46-man tribe in Colusa Country who were “confined to a little place of four acres, three acres being the old graveyard of their people.” Apparently, their only water supply was that of a 10-foot-deep well located among the graves. Their children were refused attendance at the public school and their laborers paid less than white settlers doing the same work. The indigenous people were now straddling the tenuous line between freedom and the reservation—or more symbolically, life and death.

For those who suffered the forced assimilation of President Grant’s “Peace Policy,” it meant the end of a traditional life and the beginning of their demise. Many tribes ignored the relocation orders of 1868, at which time they were forced into their parceled sections of land. This led to some of the more famous conflicts in Native American history, like the Sioux War, the Battle of Little Bighorn, and the Nez Perce War. The government had established military-like posts on government-owned land where they could create a “system of discipline and instruction,” where Indians would be “invited to assemble within these reserves.” Their “invitation,” however, looked more like a hostage situation where the Indians were rounded up at gunpoint and forced to march against their will. Best described in Janice Gould’s poem, History Lesson, it was a brutal and heartbreaking affair. “The removal has taken two weeks and of the 461 Indians that began this miserable trek, only 277 have come to Round Valley. Many died as follows: Men were shot who tried to escape. The sick or the old or women were speared if they could not keep up, bayonets being used to conserve ammunition. Babies were also killed, taken by the feet and swung against trees or rocks to crack their skulls.” This policy was subsequently regarded as a failure, mostly because it had resulted in some of the bloodiest conflicts in American history.

The way we process the past and preserve what we remember is dictated mostly by the need to protect our own sensibilities, shield us from truth’s hideous face, and give us the strength to move forward without crippling guilt about what came before. And while there is no alternative to getting beyond these atrocities—both intellectually and emotionally—it is imperative that they are seen and felt so as to never be repeated again. It is imperative that they are not overlooked simply because the total sum of our depravity is too much to continually process. This is the challenge of dark history, the test of our mettle, and one that demands the full effort of our hearts and minds—inhaling and exhaling its effect in equal measure.

And the rest is history.

I am left almost breathless with this history brought to light. One just wants to pretend human beings can not be so evil. We like to believe in kindness and caring but our history is clearly as dark as the night.

Great writing the Raven

LikeLike

This is not even 1/3 of what truly happend at this time… There is so much more: Rape ,molestation , salvery, and stolen children… .

LikeLike

There’s only so many hours in a day.

LikeLike

No does this mention Sutter and his troupe of murdering white settlers. I appreciate the history lesson, yet again the Maidu/Nisenan peoples are left out again…. This is not by far a fair account of this timeline in what you all now call California. Please feel free to leave a comment!!!

LikeLike

No where*

LikeLike

pay wandering service declare cgc13-531317

On Fri, Apr 13, 2018 at 8:50 AM, The Raven Report wrote:

> Alicia Potts commented: “No does this mention Sutter and his troupe of > murdering white settlers. I appreciate the history lesson, yet again the > Maidu/Nisenan peoples are left out again…. This is not by far a fair > account of this timeline in what you all now call California. P” >

LikeLike

GURUMAHARAJI@GURUMAHARAJI

On Fri, Apr 13, 2018 at 1:55 PM, MARIA ALCIRA LEMUS SANCHEZ wrote:

> pay wandering service declare cgc13-531317 > > On Fri, Apr 13, 2018 at 8:50 AM, The Raven Report comment-reply@wordpress.com> wrote: > >> Alicia Potts commented: “No does this mention Sutter and his troupe of >> murdering white settlers. I appreciate the history lesson, yet again the >> Maidu/Nisenan peoples are left out again…. This is not by far a fair >> account of this timeline in what you all now call California. P” >>

LikeLike

It’s an article, not a history book. But thank you for the interest. I will look into learning more about the tribes you mentioned. TRR

LikeLike

Reblogged this on WeatherEye.

LikeLike

Is there a work cited page for this article? I would love to see it in order to do some more research.

LikeLike