The notion of free will is a curious one. Philosophically speaking, the idea that we humans can exert effective control over what we do is up for debate. Sure, we can decide to go on a trip or eat pasta for dinner, but can we really decide the outcome of our baser, more fundamental actions around emotional responses, ego, and fear? Does our overall human behavior ever really change? Or does it just ebb and flow, shift and fluctuate, stretch and compensate, only to settle back in to its old patterns once again, despite our best efforts? Dark history would suggest the latter—in fact, our human flaws and misdeeds have changed very little, as the continuum of our tragic and corrupt conduct has yet to be diminished or diluted through knowledge and modernity. Despite our new age wonderment and desire to evolve, we are at our core no better than we have ever been—plagued by greed, overwhelmed by egotism, beguiled by violence, paralyzed by the unknown, and desperate for some degree of power in a universe we know—deep down inside—is far beyond our control or our understanding.

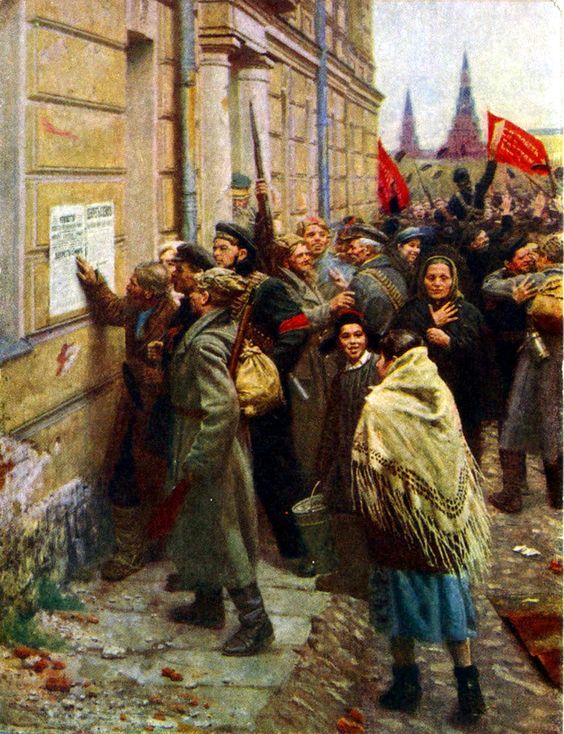

To really glimpse the horror of the human soul, we need only follow the Raven back a mere 100 years to Russia in the year 1917, arguably the most substantial period in their modern history—The Revolution that destroyed the Russian monarchy. On the surface, it was a tried and true story that’s woven itself throughout the fiber of history time and time again—a clash between the privileged few, who floated above the masses with entitled apathy, and the trampled laborers below, who scraped and scratched in desperation for a better life. It is a harbinger’s song that resonates through every culture, in every century, in every part of the world. But unlike other conflicts between the haves and have-nots, this revolt of the Russian Revolution, which rose up against the monarchy of Tsar Nicholas II, was a political explosion like no other of its century—and even more breathtaking, the backdrop to one of the most horrific and despicable mass murders of all time—the execution of the Romanov Family. A deed so foul, so grisly and dark, it not only changed the course of Russian history and exposed the sheer depravity of man’s political ambition, it left a permanently bloody mark on the physical and psychological landscape of the nation.

Not only was the Russian Revolution of 1917 an extremely violent affair, it also marked the end of absolute monarchy in the area and the creation of the Soviet Union, which eventually collapsed in 1991. Before Lenin and the Bolsheviks rose up against the existing Tsarist Autocracy, otherwise known as Imperial Russia, the region had been tightly controlled by a long list of oligarchs, despots, cabbages, and kings, all of whom were collectively known as the Grand Dukes of Moscow. Beginning with Daniel I, who inherited the area in 1283, through Yuriy Danilovich (1303) to Ivan I (1325) to Simeon (1340) to another Ivan (1353) to Dmitry of the Don (1359) to Vasily I and II, and on through about eight more puffed up peacocks until Ivan The Great, “gatherer of the Russian lands,” tripled the territory by defeating the Golden Horde and creating the Russian state. But this period only marked the beginning of a whole new slate of autocrats known as the Tsars of Russia, giving birth to ruthless despots like Ivan the Terrible, who transformed Russia from a medieval state into an empire—but also participated in many murders and massacres, beat up his pregnant daughter-in-law until she miscarried, created special frying pans for roasting his enemies alive, and stabbed his own son to death with an iron-tipped staff before giving him a mortal blow to the head in 1581.

In fact, Russian history is so complex and dramatic, it’s easy to become lost in the black hole of ambitious men, tragic decisions, and outrageous bouts of ruthlessness. But what’s worth remembering, is the way these centuries upon centuries of privileged abuse against the laboring class alchemized a certain faction, known in history as the Bolsheviks, into an iron band of angry communists who followed their leaders, Vladimir Lenin and Alexander Bogdanov, into one of the most sensational revolutions the world has ever seen. Without going down a rabbit hole of Marxism, communist manifestos, and democratic centralism, the Bolsheviks—or Reds—believed themselves to be the leaders of the Russian working class, a collection of powerful personalities who influenced the thoughts and actions of Russia’s everyday people. And sadly for the House of Romanov, who came into power in 1613 and ruled over the next three centuries with well-knowns like Peter and Catherine the Greats, the Bolshevik’s decision to annihilate Russia’s ancient monarchy arrived at precisely the same moment Tsar Nicholas II held power.

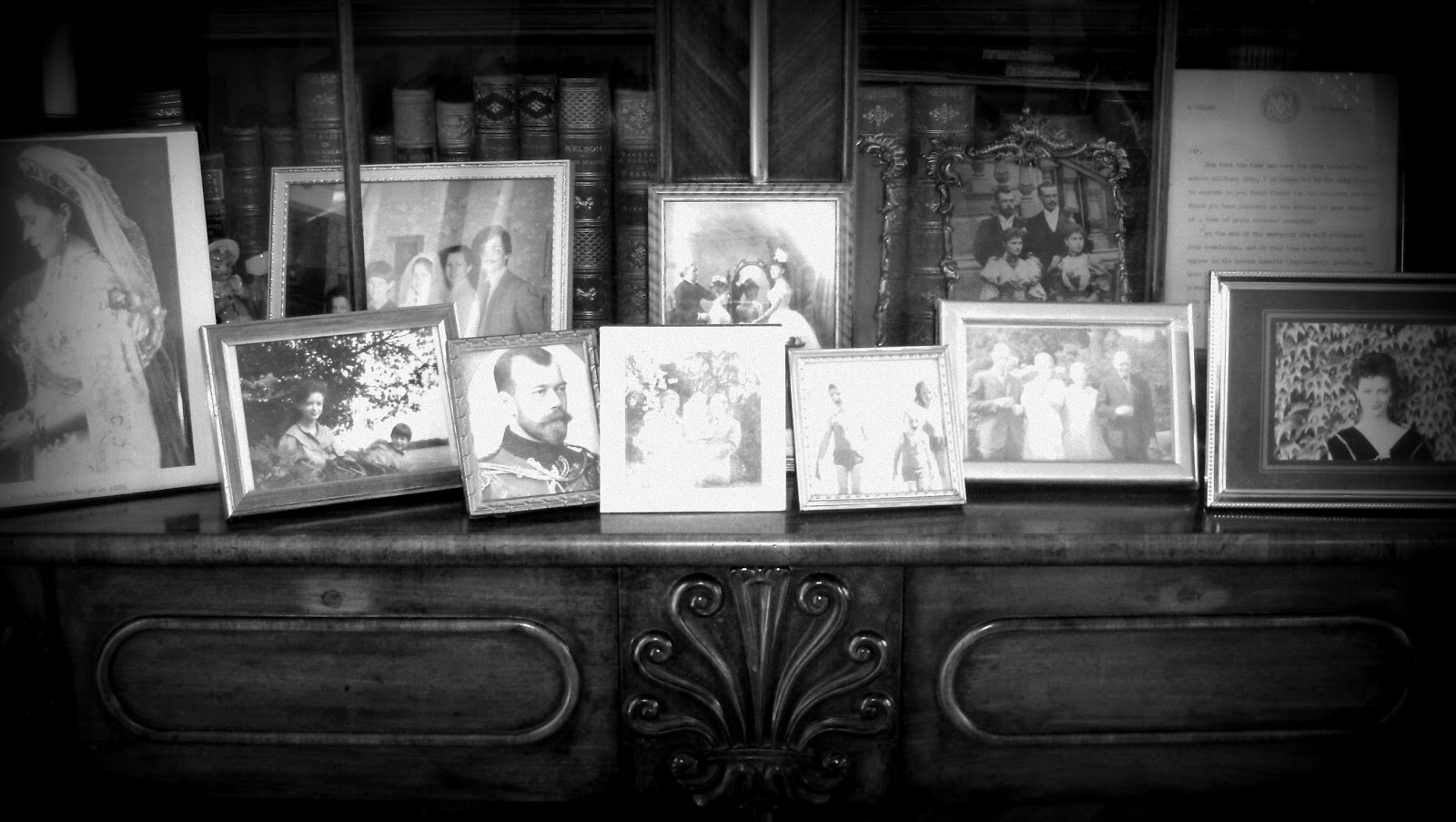

Even though it’s not really possible to fully explain or understand why the royal Romanov family was systematically dethroned and destroyed with such ghastly violence, a bit of political context does help. Tsar Nicholas II, the seated monarch during the outbreak of the revolt, hesitantly accepted the crown of a rather restless Russia in 1894 and never really found his footing as a ruler after that. In fact, it’s safe to say he was cursed from the beginning. Although he and his wife Tsarina Alexandra had five beautiful children—four daughters named Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, and one young son, Alexei—the other aspects of his life as a monarch were riddled with missteps and miscalculations. For one, the period of his coronation, which was supposed to be a festive time, was referred to as the “Khodynka Tragedy” because it led to the unseemly death of nearly 1,400 of his loyal subjects, all of whom had joined the celebration in search of free beer, brats, and souvenirs. But instead of a day filled with national pride, an estimated 1,429 of the revelers were trampled to death in a large field outside Moscow when the rush of a 500,00-person crowd turned into a massive stampede, thereby earning him the name “Nicholas the Bloody.” Ironically, the name would also suit him quite well when he departed the world forever, some 24 years later.

Even though Nicholas was a seasoned ruler when the Russian Revolution took hold, he had made several questionable decisions around the fate of the Russian people, including some screwy constitutional reforms, the massacre of nearly 100 unarmed peaceful protesters in 1905, and the decision to drag 11 million citizens into a costly and painful World War I effort, which of course they lost. And this result led to a collapse in Russian infrastructure, including its food and transportation system, along with rioting in the street. His wife Alexandra’s odd relationship with the famous mystic Rasputin didn’t help his reputation, only causing more suspicion and rancor among the public who had come to resent his political power and lack of efficacy. So, during the early stages of the Russian Revolution, Tsar Nicholas II was forced to abdicate the throne by Petrograd insurgents, and a provisional government was installed in his place. With good reason, the Romanov family feared for their safety, imploring both Britain and France to give them asylum—his wife was the granddaughter of Queen Victoria, after all—but they were refused and forced into the hands of a hostile revolutionary government.

Fearing Nicholas may try to regain power, fuel the efforts of others to do so—or worse, escape their hold, the Bolsheviks seized the imperial family and imprisoned them within the Czarskoye Selo Palace, then near the Siberian town of Tobolsk. But this captivity did not ease the insurgents’ concerns about a possible rescue, and in a secret meeting soon thereafter, Vladimir Lenin handed down a secret death sentence for the family—something the royals and the general populace never suspected. Perhaps because the Romanovs were accustomed to an opulent life at the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg or perhaps because they were delusional, Nicholas and Alexandra both refused to believe any real harm could befall them, always fostering genuine hope that they would be saved. But somewhere inside their hearts, the parents must have known their future was perilous, as 17 pounds of pounds of priceless jewelry, money, and some religious icons would later be found sewn into the clothes of their mutilated bodies.

The family’s situation was fairly idyllic at first, as they settled into their accommodations at Tobolsk with 46 court attendants, spending their days talking, studying, walking, and entertaining themselves. They were permitted to leave the house for religious services and often received courteous gifts from local townspeople who wished them well. Life was rather drab, albeit civil. But that all changed in the fall of 1917 when two new Commissioners from Lenin’s army arrived to covertly roll out his deadly decree. These social revolutionaries were much harder and more demoralizing than the previous commanders, often demonstrating vulgar disdain for the imprisoned family and their condition. The writing was on the wall; things were about to get a lot worse for the Romanovs—how bad, exactly, no one could have ever predicted.

The family who once paraded about in ermine capes, dripping with gold and diamonds, and feasting in grand rooms alive with crystal chandeliers, priceless art, brocade, velvets, mirrors, and hundred of servants, were soon moved to a dingy location known as Ipatiev House, or “The House of Special Purpose,” where they lived in small, stuffy rooms with windows sealed in filthy newspaper. To maintain some semblance of civility, however, the Reds agreed to let the Romanovs keep their four most loyal servants as well as their trusted physician, Eugene Botkin. But as time wore on, their treatment only worsened along with the political climate outside their walls. Once Lenin took hold of Russia, the constitutional democracy folded and militant communism emerged victorious. And for the Romanovs, this meant they were now in the hands of their most lethal enemies. Held hostage in grubby rooms with no way to eat, sleep, or use the bathroom with dignity, encroached, insulted, and harassed by the soldiers, the once-glittering Romanovs had been debased to no end.

Of course, the situation was worst for the Duchess Alexandra and her four daughters, who were poked and taunted through the night by guards wasted on vodka and bad temper. Although some reports suggest Maria often flirted rather innocently with her captors, a witness to the account later wrote, “The abuse reached a crescendo as the night wore on. It was dreadful, what they did.” No one really knows if the “terrified screams” of the young women were the result of fear or something much worse. Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia Romanov were beautiful, sheltered females surrounded by brutish, inebriated men who slept in the hallways, sang loud revolutionary songs, and brought in random women for sex. And although these men put on a show of revelry, they were there for one explicit purpose—to make the Romanovs suffer. So even though historians are quick to point out there’s no real evidence of sexual misconduct—in fact, some people are almost psychotically intolerant of such theories—the ugly truth is, there’s absolutely no guarantee those innocent women weren’t molested or even violently gang raped. Their secrets died along with them.

Around 1am on July 17, 1918, the family was roughly awoken and told to rise, get dressed, and prepare for another transfer to a safer location. But rather than heading towards the front door, the Romanovs were ushered down into a dank basement room where they were told to wait for their transport truck to arrive. And arrive it did—only it was packed with a squad of secret police who barrelled down into the holding room and announced, “Nikolai Alexandrovich, in view of the fact that your relatives are continuing their attack on Soviet Russia, the Ural Executive Committee has decided to execute you.” Turning to face his terrified family, Nicholas began to repeat, “What? What?” as the weapons were raised and aimed. He was the first to die in a rain of bullets, while Alexandra was shot in the head at blank range by a drunken military commissioner named Peter Ermakov. As young Maria ran for the double doors behind her, she was hit in the thigh as the room literally exploded into a chaotic cloud of smoke, executioners blindly draining their guns in all directions. They even killed Anastasia’s beloved King Charles Spaniel, Jimmy, who had she had been holding in her arms when the shooting began.

Despite the deafening sound of gunshots and falling plaster, not all the Romanovs died in the first blast of weapons, and fearing more noise would alert people on the street, the executioners began stabbing at the remaining children with their rifle bayonets, a method that quickly became too tiring, not to mention it wasn’t really working. So they pulled out their pistols once again and began shooting at the bloody children, this time aiming more pragmatically at their faces. But even after one killer guard emptied an entire magazine from his Browning gun on the 13-year old Alexie, the boy refused to die. Considering the young man suffered from hemophilia, which meant he risked greater blood loss when injured, this was a pretty astounding realization. Perhaps the shooter was hampered by inexperience or maybe nerves, but another killer named Yakov Yurovsky was forced to finish the job by giving the Romanov son one final shot to the brain.

Olga was also shot in the head while her sisters, Maria, Tatiana, and Anastasia, cowered in the corner until they too were gunned down in cold blood. And as the bodies were collected and placed on stretchers for removal, reports indicate one of the girls cried out a final time before she was brutally stabbed in the chest and then shot in the face for good measure. Subsequent investigations would reveal over 70 bullets were fired that dark night, all of which were found in the room itself and at the eerie gravesite later—where authorities also discovered signs of subsequent crimes so ghastly, they defied reason.

This gruesome scene in the basement went on for about 20 minutes as the worn-out executioners frisked the corpses for valuables and yelled back and forth about who should take the spoils and who should go send the telegram to Lenin about their success. There was some final looting of the family’s personal belongings, and the worthless items stuffed into the wood stove and burned or packed away to be sent back to Moscow for God only knows what. And then the disposal process began, for which the executioners were rather unprepared. Aside from being intoxicated, they did not have the proper vehicle to transport the heavy bodies through nine miles of marshy road on the way to Koptyaki Forest where they planned to bury the remains. When their junky Fiat truck finally arrived at the gravesite, they were met by 25 of their equally wasted compatriots, who were happy to see them, albeit somewhat disappointed the Romanov daughters had already been killed, as they had hoped for an opportunity to rape them before the burial. But making the best of a poor situation, they made due by groping the girls’ dead bodies before putting them in their graves and pulling up Alexandra’s skirts so they could finally finger the “royal cunt.”

As the injustices began to wane, the bodies were stripped naked and dumped down a mineshaft before being sprinkled with sulphuric acid to avoid future recognition. But the shaft was not as deep as they had hoped, so the absurd executioners lobbed a few grenades in the hole to expand the dirt. Alas, that didn’t work either, so they resorted to throwing as much soil and branches on top of it as possible, hoping it would avoid detection until they could come up with a better plan. After quickly locating a copper mine nearby with better depth for body disposal, the agents of death returned to the site in the middle of the night and hauled the soggy corpses from the earth using ropes and pulleys. But once again, their plan failed, as they soon became stuck in the mud on their way to the new and improved gravesite. Fearing discovery at dawn, the men hammered out a quick plan to just bury the pesky remains in a shallow 2-foot grave near the road and call it one hell of a day. But the sun was soon to rise, and there wasn’t much time.

Once the half-frozen ground had revealed enough space, the guards tossed in seven of the nine bodies and poured another hefty dose of sulphuric acid on top for safety’s sake. But at this point, their pulses must have been racing in fear of their grisly deeds, and they went one step further to hide the identities of the dead by smashing in what was left of their faces with their rifle butts and tossing on more quicklime. Resituating the same scene just 50 feet away, they proceeded to further mutilate the remaining two corpses by burning off the flesh in a bonfire and smashing the charred bones with rocks and shovels before finally—dear God, finally—burying the chalky fragments in a small hole, where they would not be found for another 89 years. What would be found the next year in 1919, however, was the first shallow mineshaft where the bodies had been removed, leaving behind a grim assortment of bone fragments, congealed fat, shoes, necklaces, belt buckles, corset stays, keys, diamonds, a severed female finger, and the dentures of Dr. Botkin. The only intact body they managed to recover at that point belonged to Jimmy the dog.

The aftermath of these barbarous deaths was multifaceted and riddled with erroneous findings, political agendas, national shame, and public fascination. Although the Soviets were ultimately forced to acknowledge the incident, Josef Stalin also tried to stifle the information by banning the reports and ordering a demolition of the Ipatiev House where the Romanovs were killed. But the public could not seem to remove the image of the fallen royals from their collective consciousness, and the affair began to take on almost mythical status. Pilgrims and monarchists who opposed the deconstruction of the empire began to visit the death sites, and a holy structure known as the Church on the Blood was built above the location where the Romanov execution took place. And in the crypt, there is a sacred chapel on the very spot of the basement room where those five children, their parents, and two courtiers experienced the ultimate horror.

Eventually, a local busybody with a penchant for primary sources and a crafty companion managed to uncover the shallow grave and pull out three skulls in 1979. But because the Romanov murders were still so politically, emotionally, and socially charged, they soon returned them to the earth rather than face possible trouble from the Russian government. When the more easygoing Mikhail Gorbachev came into power, however, the men admitted their findings to the authorities, and the nation learned the truth of the Romanov’s fate. Nonetheless, Russia still battles itself over the villainous death of the monarchs. When the last two “bodies” were found in 2007, they were confirmed to be part of the government-sanctioned murder. But still, the remains were not fully examined or used to update the historic case—instead, they were sealed inside a box within the state archives and hidden away until the Church could decide what to do. And there they sit today, waiting on God to acknowledge what no man can admit to himself.

And the rest is history.